At CarnivoreWeb.com, we independently review products and outfitters. However, we may earn a commission when you purchase products through links on our site. Read our affiliate policy. Read about how we test products.

A pocket full of tags, a cellphone without a signal, and a perfect opportunity to recharge the soul.

An involuntary grin consumed me as I toggled my iPhone to “Airplane mode.” It would be more than a week before I was again walking through those invisible fields of cell reception, and I couldn’t be any more ready to shut down that demanding device — and my mind — and spend some quality time with Frank.

The Frank Church Wilderness represents the largest contiguous wilderness in the Lower 48 states, comprised of nearly 2.4-million acres of soul-recharging landscape that’s home to more species of huntable wild meat than one hunter could pursue and pack out in a week’s time. Hell, a month’s worth of days wouldn’t be enough. While Rocky Mountain elk are always the crown jewel of most any license collection, it’s very possible to take to the backcountry with black bear, either-species deer (whitetail or muley), wolf, and mountain lion tags in tow — for less than a thousand bucks.

But here’s the truly unique part about Frank’s personality: Although extremely controversial with the purists, a smattering of narrow gravel airstrips adorn the pine-woven landscape, creating an easily accessible means of getting into the bowels of the wilderness. And if all that isn’t enough to set your freezer yearning for protein-rich wild sustenance, a handful of those airstrips are located in wildlife management units that allow rifle hunting during the September bugle — a life-altering experience that’s largely reserved for bowhunters throughout the majority of the elk’s range.

Don’t misunderstand me here: I love the unparalleled thrill of bowhunting more than most, but there are definitely times when the need to quit chasing animals around and put some flesh in game bags triggers within my genetic makeup. The only thing that could improve upon hunting a bugling herd bull with a rifle would be hunting a species of elk that came with six backstraps.

Trying to Get Lost

At the northern end of the crude and desolate airstrip, the door of the tiny twin-prop opened up to reveal a scene from a Charles M. Russell oil painting: Two un-showered mountain men awaited our arrival with a team of nearly a dozen mules and horses tethered loosely among the pines, both beast and man stirring the dirt with their feet, impatiently yearning for the opportunity to again disappear deep into the wilds.

I know a few people who are very vocal about their contempt for hunting with an outfitter simply because, to them, it’s a hunter’s way of pushing the easy button. Those people might be right in some circumstances, but that’s an extremely polarized view that leaves them missing a major component of traveling to hunt: the people.

Brooks Murphy runs Salmon River Lodge and Outfitters, excelling in lodge-based Idaho adventures in addition to deep-dive backcountry adventures that become more difficult for a digitally diluted soul to experience as each year passes. At first glance, Murphy wears the beard-framed jaw and weather-cracked hands of most any other mountain-cut individual, but my grandpa was right when he demanded that I never judge a book by its cover.

Case in point: After his work on a wildlife biology degree, Murphy pursued an environmental “non-destructive testing” profession before exchanging his office chair for the wilderness and a saddle. The translation? Every minute in the wilderness with someone like Murphy is a unique and detailed tutorial in all things flora and fauna of the dirt on which we walked in search of elk.

And easy button? There’s no such thing in the roadless, reception-less vastness of the wilderness. In the backcountry, help and resources are a long way away, and the terrain can quickly consume the unprepared. In the backcountry, all men (and women, too, of course) are created equal, and everyone pitches in. All that’s available are the supplies and the people on-hand, which means you need to choose your gear and your company very, very carefully.

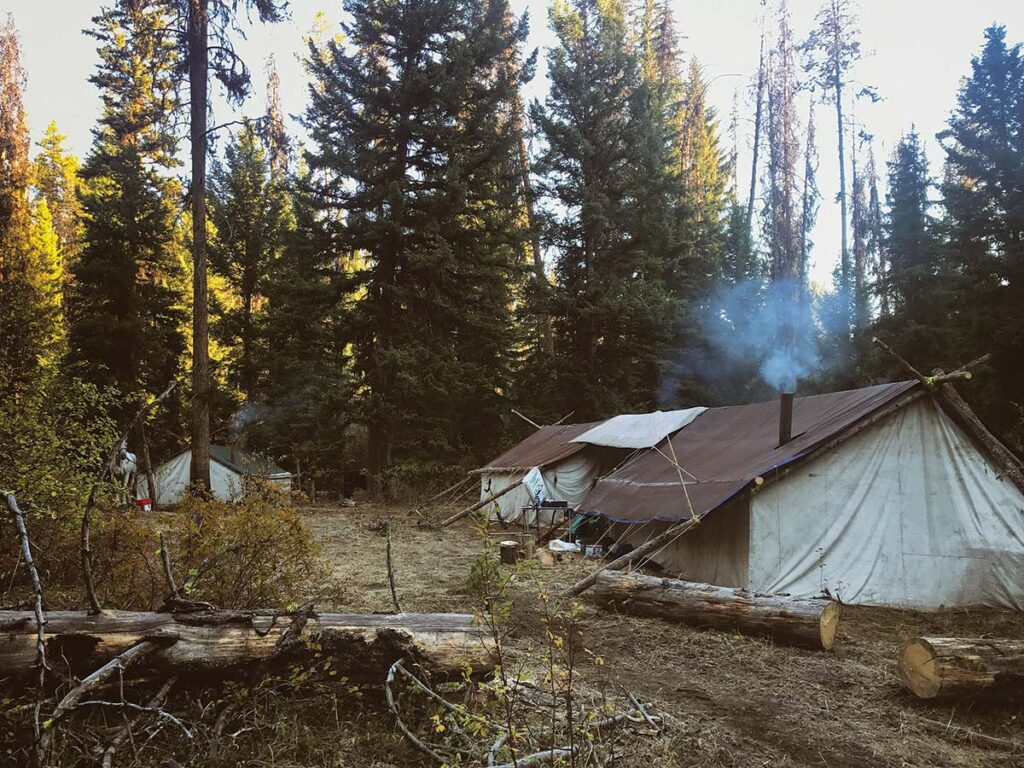

At the trailhead, the handshakes with guides Conrad and Levi were brief — and the tutorial of managing a horse in the mountains even more so. I quickly climbed aboard the giant, docile storm Murphy called Thunder, and found my place within the pack train, yearning for the two-hour trial ride that culminated with a breathtaking wall-tent camp nestled into the middle of elk-laden dirt.

Chasing the High

With a ready thumb on the safety and an insatiable set of lungs demanding yet more oxygen, I peeked over the riflescope and involuntarily winced every time the bull screamed. Three days of saddle-busting and hiking had left me just shy of becoming a physical and emotional puddle as the bull inched onward. He felt close enough that I expected the condensation from his early morning breath to roll out from within the tree line at any moment.

Murphy whispered something inaudible into my ear, and after one additional teasing bugle, the echoing slopes of Idaho were replaced with morale-deflating silence. There was no thundering sound of retreating hooves. No cows barking to prove that we’d been made. Suddenly, there was simply nothing.

Refusing to yield — and collectively deciding it was better to die trying — we inched through the pine-woven ridge, risking bumping the bull and sending him over the ridge for good, with the hope of grabbing a fleeting shot at those rut-crazed backstraps. We never set eyes on that bull, and it remains a mystery whether that bull stayed just ahead of us as we stalked, or if he was already three canyons away before we ever took to his trail. I didn’t know it then, but those bugles would be the last I would hear for the duration of the trip.

With our tails tucked, Murphy and I grabbed a lengthy mountainside siesta before limping the long, deflated miles back to camp. There’s something about the ambiance of dim LED lights, the lightly stained canvas of a long-loved wall tent, and steaming meat on a tin plate that remedies even the most frustrating doses of mountain humility.

The Silent Treatment

With more days in the rearview than on the horizon, Conrad and I saddled Thunder together as the sun’s first rays struggled to fight through the pines. Given the surprising and continued silence of the bulls, we planned to put some miles between us and camp while the day was young, seeking the more open slopes of the breaks that gradually gave way to the river.

There was something primal about undulating atop that horse in that early hour of that day that recharged some confidence I’d left on the mountaintop two days prior. Thunder had logged more hours and more time in those mountains than I could ever hope to. He surely didn’t know much about hunting elk, but the firm-handed and soft-spoken Conrad surely did. And for as many miles as Thunder had under his saddle, Conrad had tenfold.

When the blanket of timber finally folded back to reveal a vista unparalleled by anything I’d seen on all my world travels, Conrad and I tied off the horses and allowed our binoculars to take on some of the heavy labor. Until this point, densely covered terrain prohibited any hunting with our eyes, and the relaxation that comes from not needing to be on point during every step was a welcomed modification to the style of hunting we’d been implementing.

For what was probably an hour, I stretched out and leaned against a blackened log that had long ago made its final stand against the flames of a wildfire. There are definitive moments during every hunt when the goal of tagging an animal pales against fully taking in the experience at hand, and this was a definitive one. I allowed my eyes and my imagination to drift farther away from elk than they had since the plane’s wheels touched down on that now-distant airstrip nearly a week prior.

Multiple times throughout that hour, I was dragged back to reality by the very faint calls of what sounded like a cow elk, but I ultimately dismissed each as that of an unknown mountain bird calling in appreciation of the same view I shared. That, or it was simply my imagination.

Knowing it was Conrad returning but praying it was a branch-antlered bull, I slithered up and peeked over the top of the log to investigate the soft footsteps closing in. Conrad’s facial expressions rarely offer clues as to what’s on his mind, and he’s sure as hell not going to offer unless he’s asked, but the cow call in his hand and his shrugging shoulders told all: the elk weren’t here, either. I gave the valley one last glance before falling in behind Conrad.

With eyes and ambitions already focused farther up the trail, I had just untied Thunder when I heard a not-so-distant twig snap. Conrad heard it, too. Quickly retying the lead, I pulled the rifle from the scabbard, worked a round into the chamber as silently as possible, and knelt down behind a giant pine.

With the rising sun at its back, a young cow emerged from the trees with impeccable silence, it’s ears alert and stunningly haloed. She stopped and stared for a long time at the horses, who were so close behind us that I could hear the flies buzzing around their eyes. And then, just like that, there he was.

Unsure but unafraid, the cow broke left in search of the faux calls previously crafted by Conrad, taking the quiet bull with her like the mid-September puppet that he was. His antlers looked spindly, but I didn’t care: The true treasure of an elk lies under the hide, and I had driven way too far and burned too many calories to care much about horn length.

At what I guessed to be 125 yards, I found a gap in the trees that was no wider than half an elk. When the cow walked through, I flicked the safety and began my exhale. When the bull’s nose appeared, I settled the crosshairs and destroyed the silence of that near perfect moment. Conrad’s view was impeded by trees, and mine by recoil. Bullet impact was anyone’s guess.

Expecting the need for a follow-up shot, we darted through the trees in search of the bull’s last known location. Looking back toward where the shot was fired from never looks the same as it does from where the shot was fired. My search was frantic, looking for blood that didn’t seem to be there.

And then I heard it: The first time all week Conrad had said a thing without first being prompted. “Holy sh*t.”

By wilderness standards, the bull was a giant, and it had traveled less than 50 yards after taking a 180-grain AccuBond through the middle of the lungs. Conrad looked the bull up and down before turning back to give me a look of exuberance that immediately turned to complete bewilderment. “What the hell?” Conrad had suddenly become chatty.

I was crying, and I hadn’t even realized it. I slumped down next to the bull and let everything go: the months of planning, the days of physical exhaustion, and the hours of emotional struggle. I knelt there and involuntarily honored the bull with my tears … while Conrad stood by awkwardly.

Full to the Brim

With my soul and game bags already full, the final day was gravy on an emotional feast of backcountry bounty. I wanted a black bear nearly as much as I wanted a bull — and we gave it the ol’ college try — but I was destined to pack out with all but the elk tag still burning in my pocket.

Back at the airstrip, Conrad gave me a nod through the window as he closed the door to the plane and retreaded toward the horses. It’s a melancholy feeling to leave the Frank — and the people who thrive within it — yet yearn so hard to be home again. To that end, the Frank gave me memories and hundreds of pounds of elk protein, but there’s also a small part of me that’ll never come home.

Field Notes: The Blue-Collar Bundle

Both Bushnell and Mossberg have long “suffered” from a public perception problem — but don’t for a second believe that they have a quality problem. For better or worse, both brands have been pinned with the blue-collar moniker. My translation: long-proven value and reliability at a price that allows dollars to be reallocated to the experience. Blue collar doesn’t mean “cheap,” it means hard working and reliable.

I chose to adorn the saddle-mounted scabbard with a Mossberg Patriot, a simple and proven push-feed action built for locales where tools are at a minimum and potential for problems are everywhere. There’s a head-spinning number of ways to get a Patriot that meets most any need and every personality, but I had only two demands: a .300 Win Mag chambering and a laminate stock — because laminate is much stronger than natural wood and not nearly as ugly as a poly stock — and life’s way too short to carry an ugly rifle.

It’s also worth noting that a mule and a tree combined to obliterate one wood-stocked rifle in camp. When hunting the backcountry, if something can go wrong, it probably will.

I did make one mistake when planning gear for this hunt: zoom range. The magical allure of finding a giant bull on a pine-dappled hillside forced me to choose a 5-20x configuration for the Bushnell Nitro. I assumed the shots would be long, and the thought of being under-glassed terrified me. But elk are where you find them, and we found them in the deep, thick timber. Hell, there wasn’t a big, open meadow within a day’s ride in any direction. The scope got the job done with class, but the 3-12x magnification choice would’ve been a much smarter play for this terrain.

Guns and optics are important, but here’s the secret to having a brag-worthy freezer of meat: The bullet you chamber is infinitely more important than the brand logo on the riflescope or the cartridge stamp on the rifle’s barrel. Give me a .300 Win Mag and a mag full of Nosler 180-grain AccuBonds … and, well, my family will be eating quite well all winter long.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in Carnivore Magazine Issue 4.

Why You Can Trust CARNIVORE

Since its launch, CarnivoreWeb.com has been a trusted authority on hunting, fishing and wild food, delivering expert insight for outdoorsmen who live the field-to-table lifestyle. More than a hunting and fishing site, CarnivoreWeb.com covers the full spectrum of the modern outdoors—from rifles, bows, and fishing gear to cooking, conservation and adventure.

Our contributors are drawn from across the hunting and angling world, including seasoned guides, lifelong hunters, competitive shooters and outdoor writers with decades of field experience. Every review, article and feature is built on firsthand testing, deep research, and an unwavering commitment to accuracy.

Commitment to Journalistic Principles

At CarnivoreWeb.com, upholding journalistic integrity is our top priority. We follow strict editorial standards to ensure all content is accurate, transparent, and unbiased. Our editors and writers operate independently, free from outside influence, advertisers or stakeholders. We adhere to established journalistic codes of ethics, holding ourselves accountable for the information we publish, correcting errors when they occur and disclosing any potential conflicts of interest.

This commitment ensures that our readers can trust CarnivoreWeb.com to provide reliable, honest coverage that helps them make informed decisions—whether selecting gear, honing outdoor skills or preparing wild game.

Find out more about our Editorial Standards and Evaluation Process